Those words came from a young ex-IDF soldier named Ilan as we sat and gorged ourselves on delicious falafel - mine with extra hot sauce and xatzeel, eggplant - in a corner of Jerusalem's Mahaneh Yehuda market. We had just returned from Hebron, the largest city in the West Bank, home to roughly 180,000 Palestinians. Ilan, an ex-IDF soldier who served in Hebron during the Second Intifada and now leads tours with Breaking the Silence, an Israeli peace group made up of ex-IDF soldiers determined to make known the occupation's dirty work in Palestine, explains himself as he licks his fingers clean.

"Apartheid is where you have a set of laws defining discrimination between people. In Hebron, there is no law. The Israeli army is doing what they want there. They can evict Palestinians and nothing will happen. This is worse than apartheid."

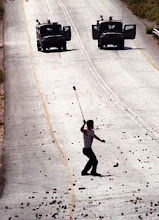

Following the Oslo Accords in 1994 and the subsequent dividing of the West Bank into three araes - full Palestinian control ("Area A", about 15% of total land), full Israeli control ("Area C", 60% of land) or joint Palestinian civil authority / Israeli military authority ("Area B", 25% of land), Hebron received special treatment. The city was divided into H1 and H2, the former being Palestinian control and the latter, Israeli. Some 30,000 Palestinians still resided in H2 at the time of partition alongside roughly 500 settlers. Today, the settlers have increased by 300 - protected by close to 3,500 soldiers and police officers - and close to half of H2's resident Palestinian population has been evicted or scared off. The city center, once a vibrant area, is now inhabited by dogs and Israeli soldiers. Almost 80% of Palestinian businesses in H2 have closed, welded shut, weeds growing from their neglected entrances. Windows, protected against settler rocks by iron gates, don't have old grandmothers peering from them anymore. As they say, it's a 'ghost town'.

"Since most Palestinians have small shops on the first floor of their homes, our strategy would be to come and close the entrances to their shops, sometimes giving a week warning, sometimes a few hours, or sometimes no warning at all," explains Ilan. "Since they couldn't enter their shops, they couldn't enter their homes, and that way, they just left."

Ilan justifies his organization's continued attempts to educate people about what the army is doing in Hebron, despite harassment, jailing and threats. "I served three years in the army and I did things I never thought I could do. I have to make up for it." For refusing to serve as an army reservist, he must serve one month out of the year in prison. (In addition to the mandatory three year army service, Israelis may be called for reserve duty for one month a year until the age of 45.) His ultra-orthodox family has shunned him; ironically, some family members from Miami send thousands of shekels every year to support the settlers in Hebron and the neighboring settlement of Kiryat Arba.

A few Palestinian businessmen who brave attacks and harassment near the Tomb of the Patriarchs/Ibrahimi mosque (a sacred site for both Jews and Muslims, a stone wall divided the structure in two parts, one mosque, one synagogue, following the 1994 massacre of Muslim worshipers by the American-Israeli doctor Baruch Goldstein), tell me that between four workers selling trinkets and pottery, they make 20 shekels a day (U$5.30). Jewish worshipers hurriedly pass by as soldiers, armed to the teeth, watch out not for settler attacks, but rather attacks against settlers. Since the army's mandate is to protect Israeli citizens, Ilan tells me that they would only intervene in attacks if the settlers were being attacked, in order to arrest Palestinians. When little settler youths throw rocks at Palestinians, the most the army can do is to reprimand them and tell them not to do that again.

Recently, in a video circulated by Israel's Channel 2, after a reported knife attack by a Palestinian against settlers in Kiryat Arba in which the attacker was shot by the IDF, a settler is seen taking his car and running over the Palestinian - twice - as police and soldiers look on idly. The tension is high here. One Palestinian I talk to claims that another Intifada is coming.

Who knows if Palestinians could endure another Intifada, but as Hebron makes clear, the status quo seems unbearable. People on both sides offer me pessimistic views of the future. As we returned to Jerusalem, we stop at the tomb of Baruch Goldstein in Kiryat Arba, overlooking the Hebron hills and guarded by an equally nutty looking fellow. The inscription on his tomb speaks volumes: "Here lies the saint... who gave his life for the Jewish people, the Torah and Israel."

---

For pictures, click here.

Saturday, December 12, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment