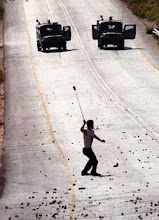

Sometimes, nowadays, as I sit around and reflect, images of Palestine come racing back. Little snapshots of times spent laughing my heart out, playing a joke; running from a low-hanging cumulous cloud of tear gas, or cursing the faceless soldier whose bullet whizzes past my face; feeling the impotence of life under occupation. There was hoola hooping with little Sarita outside her home in Sheikh Jarrah, occupied by people carrying out ‘God´s will’. For her, it was playtime; for me, a chance to break the routine of watching out for trouble, to just pretend for a second that after playing, we’ll go back into her house and I’ll sit her down on my knees in front of the TV, and everyone will be laughing and eating sweets and talking about local gossip. But that won’t happen today or tomorrow. Maybe never.

I think about this circle of violence that always seems to run through history, looping over and over again like a broken record. Around me, in my everyday immediacies, I can find examples of change, or at least some hope that things will change. A friendship, an understanding, a good community, a local butcher. Then I take a step back but the rest of the world seems to be spinning out of control. A 16 year-old boy killed in Nablus, shot in the back by another faceless soldier. Or a quiet American woman named Ellen, to whom everything seems to happen, this time finding herself on an operating table, the doctors removing a Israeli rubber bullet from her shattered wrist.

The U.S. is having disagreements with Israel over planned Jewish construction in Jerusalem! The media tells us of Israeli restraint, of the worst ‘diplomatic crisis in decades’. Do they dare remind us how a few years back, there was another ‘crisis’ when Israel planned to build in Jabal Abu Ghneim, near Bethlehem? Yes, there was a ‘crisis’ then, too. But now go to Jabal Abu Ghneim – now known mostly by its Israeli name, Har Homa – and you will see that there are no more trees, just concrete and Israeli flags. How easily we forget.

And so, we are turned again to Palestine and the Palestinians. Always this indecipherable blob of something to us. They never have the right to be individuals, just a collective enigma, a pestilent sore that won’t go away. They have no right to be lovers, fathers, sisters, dreamers, wanderers, achievers, punks. Just this body of stuff upon which history repeats itself. They aren’t allowed to break from the cycle of violence. It just happens to them.

I don’t have much to say, really; I just think too much these days. The spring is coming, to Europe, to Palestine, to Berkeley, California. There are birds outside my window. Green buds on tree branches. But I feel nervous.

There’s a little turtle in an aquarium beside me, and he is always moving about. If I put my finger in, he eagerly comes out of his shell to investigate it. He’s always scratching at the glass trying to get out. I wonder if he feels anxious.

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Belgrade 5-o

"Passports, please!"

That was the Serbian police officer's welcome as my Belgrade-Budapest train left the station. Ok, here you go. After flipping around the pages, he seemed to not find what he was looking for. He frowned, then his face lit up.

Almost smiling he said: "You are in offense. You did not register with the police after 24 hours in our country. You must get off the train with me in Novi Sad, go to the judge and pay 300 euro."

I just stared at him, disbelieving. Just what I needed. As if to prove that he wasn't lying, he asked the sobbing Swedish girl next to me (he wasn't crying for me: she had just left her boyfriend) to produce her registration card, which she did. She's a Swede, damn it, of course SHE would know that stupid law. Stupid Scandanavians.

But my police officer was already thinking.

"I will call my superior and see what I can do." He left, only to reappear after 2 minutes, still smiling. "Come with me, I am not sure I can help you. Please bring your stuff."

The other Serbian student in my cabin told me not to worry as I grabbed my stuff and followed Happy Cop #1 into the hallway. He directed me into the next cabin, which was empty. There were two options running through my head: either they were going to beat me with their batons, or mine their American treasure chest.

I looked like a total sucker.

"Well, I will try to get you a lower offense, with a lower fine. I'm trying to do everything for you, because I think you are nice." I was literally shaking out of the excitement of having to bribe a police officer. That would be fun. "Let me make another phone call." He stepped out the cabin. Through the reflection in the window, I could see him stand in the hallway, put the phone to his head, and say nothing. He returned after 45 seconds, still smiling. Cocky SOB.

"Well, I lied for you and said that you had lost your card. He said that you can pay 50 euro here on the train and no problem." Well, I admitted, I only have some 3,000 dinar on me (about 30 euro), but I also have some Macedonian money.

He didn't miss a beat. "No, that's ok, pay what you can in dinar." He wadded the bills behind his badge in his police wallet, those types that they flip open when they show you their badge and say: "POLICE. Can I take your money?" Classic.

The milking complete, the new story began, with a better ending. "You know," he relaxed into his seat. His colleague, who had been silent the entire time, continued staring out the window. "I like Americans. I just don't like your government."

"That makes two of us."

I don't think he expected that because he proceeded to interrogate me about my position on Kosovo (I don't have a strong opinion, but I toed the official line: no separatism!), about Obama (he's the same!), and Iraq and Afghanistan (where's that?). Having satisfied his curiosity, he relaxed some more. We proceeded to discuss the merits of not voting in a system where you don't have real choices. He believed that all governments were crap. My heart sang: "An anarchist! He's an anarchist! La la laa dee daa!" He was shocked to learn that we don't have universal health care in the US; he was under the impression that the empire takes everything from the rest of the world to take care of (US)Americans. I learned that the bribe I just paid him was 10% of his monthly salary; but, he exclaimed, "we here in Serbia have fun with or without money!"

The politic discussion fast melted into talk about girls, music, parties. He was really into 50cent. (What's with that? I saw 50cent concert posters all throughout the Balkans. Apparently, he is on his "Before I Self Destruct" Tour. Lame.) I told him that 50cent was crap, and he should check out Dead Prez, or maybe Immortal Technique (the image of Immortal Technique ripping off his shirt in concert to expose another shirt with a hammer and sickle made me think that Happy Cop #1 would like him.) Do I have Facebook? (After so many random people asking me to join, I feel like I MUST be missing out on something here.)

Happy Cop #2 joined in the party and played some Billy Idol on his phone. They started arguing, each telling the other to turn down the music so that I could judge which music was better (Tupac won). They liked my joke about George Bush jumping out an airplane. I honestly forgot to tell them my "a string walks into a bar" joke.

After over an hour of laughing (I am sure my previous cabin-mates next to us must have been wondering what the hell was going on), they had to leave the train at Novi Sad. We said our goodbyes. I was wondering if out of conscience, he would return the money, but he didn't. That's ok, it was worth it.

As he left, he turned around and asked me, "Are the police in America like me? I mean, do they talk to you?" I told him that generally, they blow, but there are good ones. "Are most Americans like you, really friendly?"

I thought, not usually; only when we get to bribe police officers.

That was the Serbian police officer's welcome as my Belgrade-Budapest train left the station. Ok, here you go. After flipping around the pages, he seemed to not find what he was looking for. He frowned, then his face lit up.

Almost smiling he said: "You are in offense. You did not register with the police after 24 hours in our country. You must get off the train with me in Novi Sad, go to the judge and pay 300 euro."

I just stared at him, disbelieving. Just what I needed. As if to prove that he wasn't lying, he asked the sobbing Swedish girl next to me (he wasn't crying for me: she had just left her boyfriend) to produce her registration card, which she did. She's a Swede, damn it, of course SHE would know that stupid law. Stupid Scandanavians.

But my police officer was already thinking.

"I will call my superior and see what I can do." He left, only to reappear after 2 minutes, still smiling. "Come with me, I am not sure I can help you. Please bring your stuff."

The other Serbian student in my cabin told me not to worry as I grabbed my stuff and followed Happy Cop #1 into the hallway. He directed me into the next cabin, which was empty. There were two options running through my head: either they were going to beat me with their batons, or mine their American treasure chest.

I looked like a total sucker.

"Well, I will try to get you a lower offense, with a lower fine. I'm trying to do everything for you, because I think you are nice." I was literally shaking out of the excitement of having to bribe a police officer. That would be fun. "Let me make another phone call." He stepped out the cabin. Through the reflection in the window, I could see him stand in the hallway, put the phone to his head, and say nothing. He returned after 45 seconds, still smiling. Cocky SOB.

"Well, I lied for you and said that you had lost your card. He said that you can pay 50 euro here on the train and no problem." Well, I admitted, I only have some 3,000 dinar on me (about 30 euro), but I also have some Macedonian money.

He didn't miss a beat. "No, that's ok, pay what you can in dinar." He wadded the bills behind his badge in his police wallet, those types that they flip open when they show you their badge and say: "POLICE. Can I take your money?" Classic.

The milking complete, the new story began, with a better ending. "You know," he relaxed into his seat. His colleague, who had been silent the entire time, continued staring out the window. "I like Americans. I just don't like your government."

"That makes two of us."

I don't think he expected that because he proceeded to interrogate me about my position on Kosovo (I don't have a strong opinion, but I toed the official line: no separatism!), about Obama (he's the same!), and Iraq and Afghanistan (where's that?). Having satisfied his curiosity, he relaxed some more. We proceeded to discuss the merits of not voting in a system where you don't have real choices. He believed that all governments were crap. My heart sang: "An anarchist! He's an anarchist! La la laa dee daa!" He was shocked to learn that we don't have universal health care in the US; he was under the impression that the empire takes everything from the rest of the world to take care of (US)Americans. I learned that the bribe I just paid him was 10% of his monthly salary; but, he exclaimed, "we here in Serbia have fun with or without money!"

The politic discussion fast melted into talk about girls, music, parties. He was really into 50cent. (What's with that? I saw 50cent concert posters all throughout the Balkans. Apparently, he is on his "Before I Self Destruct" Tour. Lame.) I told him that 50cent was crap, and he should check out Dead Prez, or maybe Immortal Technique (the image of Immortal Technique ripping off his shirt in concert to expose another shirt with a hammer and sickle made me think that Happy Cop #1 would like him.) Do I have Facebook? (After so many random people asking me to join, I feel like I MUST be missing out on something here.)

Happy Cop #2 joined in the party and played some Billy Idol on his phone. They started arguing, each telling the other to turn down the music so that I could judge which music was better (Tupac won). They liked my joke about George Bush jumping out an airplane. I honestly forgot to tell them my "a string walks into a bar" joke.

After over an hour of laughing (I am sure my previous cabin-mates next to us must have been wondering what the hell was going on), they had to leave the train at Novi Sad. We said our goodbyes. I was wondering if out of conscience, he would return the money, but he didn't. That's ok, it was worth it.

As he left, he turned around and asked me, "Are the police in America like me? I mean, do they talk to you?" I told him that generally, they blow, but there are good ones. "Are most Americans like you, really friendly?"

I thought, not usually; only when we get to bribe police officers.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

The Mystery Land of No Borders

At 5:57 in the morning, I managed to crawl into the train leaving the Thessaloniki station. I don't know how I did it, but somehow I managed to avoid a repeat of Barcelona New Year's 2009 fiasco, when I fell asleep at the airport gate, just missing my flight to Milan. At the Macedonian border, I got out to breathe some of that cold, crisp air. I sat down and enjoyed the scenery and pondered in my drunken bliss. We had partied all through the night. I felt like a silly 20-yr old again. Then those happy memories of me and Taz singing "Billy Jean", wearing transparent food-handling gloves, drunk on Greek chipero, shots of tequila and amaretto (so classy!), in some Thessaloniki karaoke bar suddenly turned into a moving train, marching on, leaving me behind...

It was the train. I ran and somehow managed to open the door and jump in as the platform pulled away behind me. My fellow passengers seemed relieved that I had made it, but my avalanching hangover only permitted a meek smile in response. We were now in Macedonia, Skopje-bound, racing along those railway lines that once stitched together Tito's vision of an ethnically diverse yet harmonious Yugoslavia. A dream that seemed to just fall to pieces...

The Balkans. I never imagined coming out here. Least of all ordering something called "Pig Hunger" from a small Skopjan restuarant. Don't worry, it turned out to be be just a piece of deep fried pork with french fries, and I tell you, it's the breakfast of champions. My goal was to get to Sarajevo, and I was told by the curious ticket saleswoman that I could 'simply' take a bus to Pristina and from there, anything is possible. Yes. My last memory before I passed out again in the bus station was: "Who is this woman across from me reading 'The Audacity of Hope'?"

1:18. I wake up and realize that the bus is leaving in 2 minutes and I don't know where I am. I'm only thinking "No more Barcelona!". I managed to find my bags at the locker and run to the bus and hop in. I've forgotten my manners. No "Buenas" greeting to everyone in the bus. But that's ok, they don't speak Spanish.

We pass another border, this one somewhat more contested that the Greek-Macedonian one. We are entering the "Free-World's" newest country... ladies and gentlemen, introducing Kosovo. One thing I will realize on the rest of my trip is that border stamps seem to be arbitrary. It's as though old Yugoslavia still exists, and I am just passing from one area to the other. What used to be areas of a federation are now countries! Imagine if Florida became it's own country (then we could bomb Little Havana...). But when I leave Macedonia, I get no stamp, nor do I get one entering Kosovo, or leaving it. I don't get one leaving Montenegro or leaving Bosnia. What the hell is this?

Back to the story. Still with me? Kosovo is a mass of mountains and mines. I meet a frustrated Italian furniture salesman ("Cazzo! These people don't know real style!") who tells me that parts of Kosovo used to yield three crops a year. Other than that, at least in the winter, it is snow and mud and yuck. Or maybe that was my hangover still clouding my judgement.

But about 2 hours south of Pristina, I wake up as the bus stops. One man speaking English with an Eastern European accent gets off the bus, followed by an African American dude with a red bandana and a growing belly. His accent and demeanor catch my attention. A fellow traveler? I watch him as he exits the bus, looks around, and smiles at some men in a car who were waiting for him. The Eastern European has already left. The bus pulls off.

I connect some dots later. The town we pass after the 'drop-off' is Ferizaj. The biggest employer in Ferizaj, and undoubtedly all of Kosovo, is right there: US Camp Bondsteel. I've heard rumors that you can see it from space. One of the US' big wins from the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo and the ensuing NATO bombing of Serbia was Camp Bondsteel, built by Kellogg, Brown and Root (KBR; similar to Halliburton) and destined to replace US 'tenancy' of German and other European bases (as focus shifts more on the Middle East and its oil). In fact, that little train from Thessaloniki to Skopje most likely passed over a network of pipelines, all of which is neatly under Camp Bondsteel's 7,000-man watch. I remember reading an article a few years back about how US military bases in the Balkans, namely Kosovo, were acting as mini-Guantamo's in the US 'War on Terror'. It made me think what those Americans in civilian clothing were doing out there. It's understandable why the Americans were so eager for Kosovan independence, and why some Serbs still still hate America (we also bombed them in 99 and put them under sanctions, Iraq-style), though we still claim that our Kosovo intervention was purely humanitarian, even "charity" or a "mission to civilize the Serbs". A sign outside the bus station in Pristina waves an American flag and in big, bold letters: "Bill Clinton".

The only interaction I had with an angry Serb was in a small village 2km away from the site of the July 1995 Srebrenica massacre, where over 8,000 Muslims were exterminated. (While Bill Clinton kept up an arms embargo on the Bosnian Muslims at the beginning of the 90s, he was at least able to send over $1 million for a memorial. Thanks, Bill!) Afterwards, returning to the town of Bratunac, I had talked with an Austrian master sergeant of the LOT EUROFOR observer mission who told me that while this area used to be Muslim, under the Dayton Accords which pacified the tensions, Serbs were allowed to take over, and now account for over 90% of the population. However, the two groups "don't fight anymore. Sometimes they argue, but that's normal."

Mind you, I was in Republika Srpska, the autonomous region of the Federation of Bosnia and Hercegovina, dominated by Serbs. (Republika Srpska practically covers half, or more than half, of Bosnia, if you eyeball the map.) Eyes had been watching me then, as they had while I ate Serbian goulash and read a biography of Tito. As I waited in the bus station, a middle-aged police officer in a leather jacket with the insignia of Republika Srpska approached me and asked for my passport. The other passengers watched on curiously. "American? Huff!" he exclaimed. He took my passport for further inspection, though he really didn't know what to do with it. Just to show that Americans are not too appreciated. (Many Serbs acknowledge that while they did wrong, their grievances weren't understood...). I just smiled and thought about how stupid cops were.

But that was the only incident. Here in Belgrade people have been warm and friendly, and understand that it was "the government, not the people". We carried out collective punishment, collateral damage, for the crimes of Milosevic. They wisely point out Iraq and Afghanistan. My friends here lived under sanctions, and remember how a 500,000,000,000 dinar note was once printed, a doctor's monthly salary could buy a liter of gas and the only shows on TV were Mexican soaps like "Cassandra". I can imagine why now, young people just want to party and have fun. Last night we hitch-hiked through Belgrade, getting rides with two young potato salesmen and some young punks hotboxing their car, and ended up in some weird Goth, Rammstein-blaring rave/bondage underground bar. As we took the bus back home, the rising sun cast its rays on an old bombed out building, 5 minutes from the American Embassy, unexploded NATO bombs still inside the wreckage. Apparently, the Serbs don't have the expertise to defuse them, and the Americans haven't sent over a team yet.

It was the same in Sarajevo, the city where Gavrilo Princip and the "Black Hand" triggered WWI with the magnicide of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife. I walked past the market where a bomb killed 68 civilians (its disputed if Bosnian rebels purposefully killed their own people, or it was the Serbs who were laying seige to the city for 4 years), past the bullet-ridden stores and homes, the rebuilt mosques and churches. Maybe 10,000 people died or went missing in the city alone. People are tired of war, they want to move on. Ironically, there is a debate in Serbia whether or not to join NATO (!). I was told by the Italian that the only calm place is in Montenegro; my memory is a 2am bus station bar in Podgorica, sleeping at a table, while old, toothless men boozed up on Montenegran Rakija (close to vodka, or Greek ouzo, or Colombian aguardiente... I am becoming an expert). Seemed calm enough.

I recommend seeing "Lepa Sela, Lepo Gore" (Pretty Village, Pretty Flame). It's by a Serbian director, and while I think it still is biased (the Muslim protagonist in the end seems darker and more evil, while the Serb protagonist remains white, albeit with a mixed conscience), it does a fairly good job of relating the reality. (Much better than "Hurt Locker", which made me almost throw up.)

That's enough long writing. Wherever I go, I meet amazing people, generous with time and smiles. They've lived war and conflicts, poverty and revolution, and they manage to keep going. Despite all the politicking, the backstabbing, the collateral damage and the deceit, they continue. Trying to be happy and being normal amidst the madness can be a pretty revolutionary thing.

Hasta pronto...

It was the train. I ran and somehow managed to open the door and jump in as the platform pulled away behind me. My fellow passengers seemed relieved that I had made it, but my avalanching hangover only permitted a meek smile in response. We were now in Macedonia, Skopje-bound, racing along those railway lines that once stitched together Tito's vision of an ethnically diverse yet harmonious Yugoslavia. A dream that seemed to just fall to pieces...

The Balkans. I never imagined coming out here. Least of all ordering something called "Pig Hunger" from a small Skopjan restuarant. Don't worry, it turned out to be be just a piece of deep fried pork with french fries, and I tell you, it's the breakfast of champions. My goal was to get to Sarajevo, and I was told by the curious ticket saleswoman that I could 'simply' take a bus to Pristina and from there, anything is possible. Yes. My last memory before I passed out again in the bus station was: "Who is this woman across from me reading 'The Audacity of Hope'?"

1:18. I wake up and realize that the bus is leaving in 2 minutes and I don't know where I am. I'm only thinking "No more Barcelona!". I managed to find my bags at the locker and run to the bus and hop in. I've forgotten my manners. No "Buenas" greeting to everyone in the bus. But that's ok, they don't speak Spanish.

We pass another border, this one somewhat more contested that the Greek-Macedonian one. We are entering the "Free-World's" newest country... ladies and gentlemen, introducing Kosovo. One thing I will realize on the rest of my trip is that border stamps seem to be arbitrary. It's as though old Yugoslavia still exists, and I am just passing from one area to the other. What used to be areas of a federation are now countries! Imagine if Florida became it's own country (then we could bomb Little Havana...). But when I leave Macedonia, I get no stamp, nor do I get one entering Kosovo, or leaving it. I don't get one leaving Montenegro or leaving Bosnia. What the hell is this?

Back to the story. Still with me? Kosovo is a mass of mountains and mines. I meet a frustrated Italian furniture salesman ("Cazzo! These people don't know real style!") who tells me that parts of Kosovo used to yield three crops a year. Other than that, at least in the winter, it is snow and mud and yuck. Or maybe that was my hangover still clouding my judgement.

But about 2 hours south of Pristina, I wake up as the bus stops. One man speaking English with an Eastern European accent gets off the bus, followed by an African American dude with a red bandana and a growing belly. His accent and demeanor catch my attention. A fellow traveler? I watch him as he exits the bus, looks around, and smiles at some men in a car who were waiting for him. The Eastern European has already left. The bus pulls off.

I connect some dots later. The town we pass after the 'drop-off' is Ferizaj. The biggest employer in Ferizaj, and undoubtedly all of Kosovo, is right there: US Camp Bondsteel. I've heard rumors that you can see it from space. One of the US' big wins from the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo and the ensuing NATO bombing of Serbia was Camp Bondsteel, built by Kellogg, Brown and Root (KBR; similar to Halliburton) and destined to replace US 'tenancy' of German and other European bases (as focus shifts more on the Middle East and its oil). In fact, that little train from Thessaloniki to Skopje most likely passed over a network of pipelines, all of which is neatly under Camp Bondsteel's 7,000-man watch. I remember reading an article a few years back about how US military bases in the Balkans, namely Kosovo, were acting as mini-Guantamo's in the US 'War on Terror'. It made me think what those Americans in civilian clothing were doing out there. It's understandable why the Americans were so eager for Kosovan independence, and why some Serbs still still hate America (we also bombed them in 99 and put them under sanctions, Iraq-style), though we still claim that our Kosovo intervention was purely humanitarian, even "charity" or a "mission to civilize the Serbs". A sign outside the bus station in Pristina waves an American flag and in big, bold letters: "Bill Clinton".

The only interaction I had with an angry Serb was in a small village 2km away from the site of the July 1995 Srebrenica massacre, where over 8,000 Muslims were exterminated. (While Bill Clinton kept up an arms embargo on the Bosnian Muslims at the beginning of the 90s, he was at least able to send over $1 million for a memorial. Thanks, Bill!) Afterwards, returning to the town of Bratunac, I had talked with an Austrian master sergeant of the LOT EUROFOR observer mission who told me that while this area used to be Muslim, under the Dayton Accords which pacified the tensions, Serbs were allowed to take over, and now account for over 90% of the population. However, the two groups "don't fight anymore. Sometimes they argue, but that's normal."

Mind you, I was in Republika Srpska, the autonomous region of the Federation of Bosnia and Hercegovina, dominated by Serbs. (Republika Srpska practically covers half, or more than half, of Bosnia, if you eyeball the map.) Eyes had been watching me then, as they had while I ate Serbian goulash and read a biography of Tito. As I waited in the bus station, a middle-aged police officer in a leather jacket with the insignia of Republika Srpska approached me and asked for my passport. The other passengers watched on curiously. "American? Huff!" he exclaimed. He took my passport for further inspection, though he really didn't know what to do with it. Just to show that Americans are not too appreciated. (Many Serbs acknowledge that while they did wrong, their grievances weren't understood...). I just smiled and thought about how stupid cops were.

But that was the only incident. Here in Belgrade people have been warm and friendly, and understand that it was "the government, not the people". We carried out collective punishment, collateral damage, for the crimes of Milosevic. They wisely point out Iraq and Afghanistan. My friends here lived under sanctions, and remember how a 500,000,000,000 dinar note was once printed, a doctor's monthly salary could buy a liter of gas and the only shows on TV were Mexican soaps like "Cassandra". I can imagine why now, young people just want to party and have fun. Last night we hitch-hiked through Belgrade, getting rides with two young potato salesmen and some young punks hotboxing their car, and ended up in some weird Goth, Rammstein-blaring rave/bondage underground bar. As we took the bus back home, the rising sun cast its rays on an old bombed out building, 5 minutes from the American Embassy, unexploded NATO bombs still inside the wreckage. Apparently, the Serbs don't have the expertise to defuse them, and the Americans haven't sent over a team yet.

It was the same in Sarajevo, the city where Gavrilo Princip and the "Black Hand" triggered WWI with the magnicide of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife. I walked past the market where a bomb killed 68 civilians (its disputed if Bosnian rebels purposefully killed their own people, or it was the Serbs who were laying seige to the city for 4 years), past the bullet-ridden stores and homes, the rebuilt mosques and churches. Maybe 10,000 people died or went missing in the city alone. People are tired of war, they want to move on. Ironically, there is a debate in Serbia whether or not to join NATO (!). I was told by the Italian that the only calm place is in Montenegro; my memory is a 2am bus station bar in Podgorica, sleeping at a table, while old, toothless men boozed up on Montenegran Rakija (close to vodka, or Greek ouzo, or Colombian aguardiente... I am becoming an expert). Seemed calm enough.

I recommend seeing "Lepa Sela, Lepo Gore" (Pretty Village, Pretty Flame). It's by a Serbian director, and while I think it still is biased (the Muslim protagonist in the end seems darker and more evil, while the Serb protagonist remains white, albeit with a mixed conscience), it does a fairly good job of relating the reality. (Much better than "Hurt Locker", which made me almost throw up.)

That's enough long writing. Wherever I go, I meet amazing people, generous with time and smiles. They've lived war and conflicts, poverty and revolution, and they manage to keep going. Despite all the politicking, the backstabbing, the collateral damage and the deceit, they continue. Trying to be happy and being normal amidst the madness can be a pretty revolutionary thing.

Hasta pronto...

Friday, March 12, 2010

Decisions

Yesterday, long after the 20,000-strong march through Thessaloniki had ended, and chants were replaced by car horns, and the tear gas had dissolved over the sea, and the rock I warmed in my pocket had long since taken flight, I found myself sitting at the train station. No buying tickets to Skopje: the railway employees were on strike. (Greek newspapers put strike participation around 90%. Pretty impressive.)

As I sat, I saw a Greek taxi driver trying to understand a man who was pleading for help in Arabic. Two young kids approached me, greeting me with "salaam aleikum". They were Afghanis. Gesturing for my phone, they said "Missed call!" The smallest of the two had a fresh pink scar under his right eye, but seemed to be always smiling.

As they made their missed call (93 country code IS Afghanistan, right?), the Syrian man approaches me and asks if I speak Arabic. Imagine my surprise when he showers me with kisses when I understand him. The story: they have all - there are more immigrants inside the station - been let of out jail yesterday night after spending over a month in prison. When they were arrested at the Turkish border, the police, claiming they were 'mafiosos', confiscated all their money, and took the batteries out of their cell phones. They released them at the Thessaloniki train station. I thought about Amadeu Casellas, the Spanish anarchist jailed for robbing banks to fund workers' struggles, who was released around the same time.

There were also some Algerians and Syrians who later came up to me. We talked about Palestine. I remembered 14-year old Ehab who lays in a coma after the Israelis shot him in the head in An-Nabi Salih. They had traveled far, only to be stuck in the 'doorway to Europe' and they hated Greece.

The story quickly dissolved into attempts to get 'a brother' to send money from Germany via Western Union through my name. Phone calls. Missed calls. Food. Taking pictures. I talked to young Sarah on the other line who was supposed to be the niece of the Syrian man, but didn't know him and was terrified that he was yelling at her to get her father. I tried to talk to her. "Spricken Deutsch?" I wasn't sure why I asked that, because I don't speak any German myself. But she responded in Arabic, "my father isn't home." The Syrian was getting hysterical and I was starting to get annoyed with him. What else COULD he be? What else could I do?

The Greek taxi driver came up to me after awhile and asked why I was doing all of this. I replied that wherever I had been, people had helped me, so why shouldn't I help them? He told me about how he once helped some Afghan immigrants and they jumped out of his car without paying, after he had driven them down from Thessaloniki. Yes, I said, anything can happen.

I said goodnight to Europe's newest economic and political refugees, and promised to return this morning to see if we would have any success with Western Union. I asked a Palestinian kid who had a few euros on him if he would leave to Athens, where he had a contact. He said that he would wait until everyone was ok. Solidarity?

In the morning, the Afghans were gone. Their missed call to Afghanistan had called back with contacts for Athens. The Athens friend had contacted and had somehow helped them. I was happy. At least one good story. A young Algerian was ecstatic that the card I bought him allowed him to talk to his sick mother. The Palestinian was still there.

And the Syrian was passing between bouts of depression and anger. He frustration at times turned on me when I couldn't understand everything he was saying. We walked to Western Union, followed by a North African - presumably Algerian - who claimed to be Syrian. Algeria asked me:

"Are you Muslim?"

I winced at the question, because I hated getting it, but I knew how to respond, and everyone who had ever asked me didn't mind my reply.

"No."

His smile faded. "Fi muskila?" I asked if there was a problem.

"Yes. Fi mushkila."

I looked away as the Syrian man yelled at him. His defense of me didn't prevent me from wanting to smash the Algerian. The Algerian quietly said he was joking and patted me on the back, but I didn't say anything. I didn't want religion and their anger at the West to be played out on me, but could I help it? Could he help zealously being proud of the last thing that gave him a shred of dignity over the sleepless nights, the jail, the hunger and the dirt? The Palestinian had asked me if lying to an Orthodox priest - they told him that they were Christian Arabs in order for him to give them food - was bad. I had told them that he may have given it even if he knew they were Muslim. He disagreed. Inside, I questioned myself: had the priest known, would he have helped?

The Algerian played his hand at asking for cigarettes. I refused. I could imagine the anti-immigrant debaters laughing at me. You sucker, they are taking advantage of you! They are all the same!

I wanted to run, to leave them and never come back. To not care about what happened with them. There were thousands of people rotting all over the world, trying to survive, why the hell should I take care of these people? I still don't know. Maybe another day I would have seen them in the train station and not paid attention. Maybe I would be in a rush. Maybe I would be that person walking with his girlfriend, too in love to see the misery of the world. Maybe I would be that traveler in two days passing by them with my bags on my way to Skopje, passport in hand, ready to have a new adventure.

In about 40 minutes, I leave to go back and find out if we can do the Western Union deal again. I'm nervous. What else can I feel?

http://www.immigrantsolidarity.org

As I sat, I saw a Greek taxi driver trying to understand a man who was pleading for help in Arabic. Two young kids approached me, greeting me with "salaam aleikum". They were Afghanis. Gesturing for my phone, they said "Missed call!" The smallest of the two had a fresh pink scar under his right eye, but seemed to be always smiling.

As they made their missed call (93 country code IS Afghanistan, right?), the Syrian man approaches me and asks if I speak Arabic. Imagine my surprise when he showers me with kisses when I understand him. The story: they have all - there are more immigrants inside the station - been let of out jail yesterday night after spending over a month in prison. When they were arrested at the Turkish border, the police, claiming they were 'mafiosos', confiscated all their money, and took the batteries out of their cell phones. They released them at the Thessaloniki train station. I thought about Amadeu Casellas, the Spanish anarchist jailed for robbing banks to fund workers' struggles, who was released around the same time.

There were also some Algerians and Syrians who later came up to me. We talked about Palestine. I remembered 14-year old Ehab who lays in a coma after the Israelis shot him in the head in An-Nabi Salih. They had traveled far, only to be stuck in the 'doorway to Europe' and they hated Greece.

The story quickly dissolved into attempts to get 'a brother' to send money from Germany via Western Union through my name. Phone calls. Missed calls. Food. Taking pictures. I talked to young Sarah on the other line who was supposed to be the niece of the Syrian man, but didn't know him and was terrified that he was yelling at her to get her father. I tried to talk to her. "Spricken Deutsch?" I wasn't sure why I asked that, because I don't speak any German myself. But she responded in Arabic, "my father isn't home." The Syrian was getting hysterical and I was starting to get annoyed with him. What else COULD he be? What else could I do?

The Greek taxi driver came up to me after awhile and asked why I was doing all of this. I replied that wherever I had been, people had helped me, so why shouldn't I help them? He told me about how he once helped some Afghan immigrants and they jumped out of his car without paying, after he had driven them down from Thessaloniki. Yes, I said, anything can happen.

I said goodnight to Europe's newest economic and political refugees, and promised to return this morning to see if we would have any success with Western Union. I asked a Palestinian kid who had a few euros on him if he would leave to Athens, where he had a contact. He said that he would wait until everyone was ok. Solidarity?

In the morning, the Afghans were gone. Their missed call to Afghanistan had called back with contacts for Athens. The Athens friend had contacted and had somehow helped them. I was happy. At least one good story. A young Algerian was ecstatic that the card I bought him allowed him to talk to his sick mother. The Palestinian was still there.

And the Syrian was passing between bouts of depression and anger. He frustration at times turned on me when I couldn't understand everything he was saying. We walked to Western Union, followed by a North African - presumably Algerian - who claimed to be Syrian. Algeria asked me:

"Are you Muslim?"

I winced at the question, because I hated getting it, but I knew how to respond, and everyone who had ever asked me didn't mind my reply.

"No."

His smile faded. "Fi muskila?" I asked if there was a problem.

"Yes. Fi mushkila."

I looked away as the Syrian man yelled at him. His defense of me didn't prevent me from wanting to smash the Algerian. The Algerian quietly said he was joking and patted me on the back, but I didn't say anything. I didn't want religion and their anger at the West to be played out on me, but could I help it? Could he help zealously being proud of the last thing that gave him a shred of dignity over the sleepless nights, the jail, the hunger and the dirt? The Palestinian had asked me if lying to an Orthodox priest - they told him that they were Christian Arabs in order for him to give them food - was bad. I had told them that he may have given it even if he knew they were Muslim. He disagreed. Inside, I questioned myself: had the priest known, would he have helped?

The Algerian played his hand at asking for cigarettes. I refused. I could imagine the anti-immigrant debaters laughing at me. You sucker, they are taking advantage of you! They are all the same!

I wanted to run, to leave them and never come back. To not care about what happened with them. There were thousands of people rotting all over the world, trying to survive, why the hell should I take care of these people? I still don't know. Maybe another day I would have seen them in the train station and not paid attention. Maybe I would be in a rush. Maybe I would be that person walking with his girlfriend, too in love to see the misery of the world. Maybe I would be that traveler in two days passing by them with my bags on my way to Skopje, passport in hand, ready to have a new adventure.

In about 40 minutes, I leave to go back and find out if we can do the Western Union deal again. I'm nervous. What else can I feel?

http://www.immigrantsolidarity.org

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Greece on the Move

First of all, Happy International Women's Day... belatedly.

Most of my week here in Thessaloniki has been surprisingly not-Greek oriented. I've been learning more about the past (and present) conflicts in the Balkans rather than conflicts here in Greece. Well, we do what we can. So much of the news has not been dedicated to the general strikes happening around the country, but rather to the Greek Paris Hilton: Julia. (If you do a Google search of "Julia Greece", you can download the singer's porn video that is so shocking Greece.)

Thessaloniki is not the picturesque Greek I expected, or that we see in the movies or travel guides (duh). It's a fairly large port city whose streets resemble Barcelona's L'Eixample neighborhood, albeit with narrower streets and far more traffic. And it's cold now, the wind really bites into your face as you walk down Nikis (Victory) Boulevard, past the statue of Alexander the Great (one dispute Greece has with neighboring Macedonia is that the name Macedonia is part of Greek heritage and can't be used by a largely Slavic population... boring) and the "White Tower". The White Tower is the symbol of Thessaloniki. It was an Ottoman Empire-age prison whose stone walls used to be stained red with the blood of executed prisoners who were hung from the cornice. It was whitewashed after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

One thing I miss about the Middle East was not having to do street battle with my arch-nemesis: dog shit. It's bountiful here.

'

'

I'm reading a book right now called "Unholy Alliance", about Greece's alliance with Milosevic's Serbia. Greece was the only NATO and EU-member nation that supported (and very much openly so) the Serbs during the Balkan wars. The author, reknowned Greek journalist Takis Michas, claims that this alliance was due in part to religion and a shared sense of history. Both Serbs and Greeks are Orthodox, and viewed the wars as an attack by the Muslim Crescent (with Greek's arch-rival, Turkey, somewhere in the background pulling the strings) and the Catholics (the Croats, Vatican, etc.). Serb chetniks helped defend against Nazi occupation during WWII. And something about ancient kingdoms allying at the border of the Ottoman and Hapsburg empires. Greek Orthodox priests visited and prayed with Greek paramilitary units working alongside Serb Chetnik forces, the same forces who committed some 90% of human rights violations during the war. In short, Greece likes Serbia.

In setting up an understanding of this alliance, Michas describes early in his book three facets of Greek ethnic nationalism (which he opposes to civic nationalism, or being Greek based on universal citizenship rights). Religion (Greeks hold on to the uniqueness of their Greek Orthodoxy), shared geneology (the Hellenic culture) and language (Greek).

I mentioned to my friend that this type of nationalism, in my opinion, was similar to that experienced in Israel, where language, shared geneology and religion plays a big factor in "Israeli" collective identity. If you are not able to fully enjoy these three qualities, you are not really Israeli. Just ask any Arab citizen of Israel. Al-Jazeera reported recently on Israel's immigrants, many of them children born and bred in Israel, who may be deported at the end of the summer back to their countries of origin.

My friend didn't much like the comparison, but questioned how someone who wasn't "really Greek" could become a citizen; with so few Greeks (11 million), allowing so many immigrants in would make Greece "less Greek". Apparently, she is on the conservative side of the debate that is raging over the PASOK (socialist) government's proposal to grant citizenship to all their immigrants. A good article by Douglas Muir points out that even the current Archbishop of Athens (the head of the Greek Orthodox Church), is actually an "Arvanite", ethnic Albanians incorporated into the Greek state at the time of independence. No one even realizes this, and he points it out to show that Greek culture is not static and is capable of admitting many cultures and still retaining its identity.

To be fair, proportionately, in seems as though Greece is taking in the lion's share of undocumented workers. For a cash-strapped country, that can cause a heavy burden. (UPDATE: Thanks to Carmen for pointing out the idiocy of this previous statement.In her words, "anti immigrant movements are racist and always have been." I agree and pardon the previous statement). I remember as I crossed the Turkey-Greece border, there was one black youth on our bus. As soon as we entered Greece, I knew there would be problems when the border police started looking at him sternly. He was taken off the bus and detained, on the suspicion that his passport was fake.

Of course, not everyone shares my friend's point of view. Last year, after a Pakistani youth died in police custody, people took to the streets and battled the police. At least among the anarchists, it was seen as another example of the police brutality that caused massive rioting in December 2008. On March 20th, there will be demonstrations held for allowing immigrants - children especially - to become citizens.

Greek society seems to be super dynamic, and changing everyday. The strikes called against the EU and the privatization schemes as a response to the debt are constants. There was an uproar over a recent suggestion by German MPs that Greece should sell some of their islands, an overtly imperialist and patronizing statement that sent Greeks running around rumoring a second German occupation of the nation. This Thursday is another strike here in Thessaloniki and I'll be sure to be there.

Meanwhile, popular 'expropriations' of food are still being carried out against large supermarket chains, and in Robin Hood style, the goods are being distributed in needy communities. Enjoy the video!

Most of my week here in Thessaloniki has been surprisingly not-Greek oriented. I've been learning more about the past (and present) conflicts in the Balkans rather than conflicts here in Greece. Well, we do what we can. So much of the news has not been dedicated to the general strikes happening around the country, but rather to the Greek Paris Hilton: Julia. (If you do a Google search of "Julia Greece", you can download the singer's porn video that is so shocking Greece.)

Thessaloniki is not the picturesque Greek I expected, or that we see in the movies or travel guides (duh). It's a fairly large port city whose streets resemble Barcelona's L'Eixample neighborhood, albeit with narrower streets and far more traffic. And it's cold now, the wind really bites into your face as you walk down Nikis (Victory) Boulevard, past the statue of Alexander the Great (one dispute Greece has with neighboring Macedonia is that the name Macedonia is part of Greek heritage and can't be used by a largely Slavic population... boring) and the "White Tower". The White Tower is the symbol of Thessaloniki. It was an Ottoman Empire-age prison whose stone walls used to be stained red with the blood of executed prisoners who were hung from the cornice. It was whitewashed after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

One thing I miss about the Middle East was not having to do street battle with my arch-nemesis: dog shit. It's bountiful here.

'

'I'm reading a book right now called "Unholy Alliance", about Greece's alliance with Milosevic's Serbia. Greece was the only NATO and EU-member nation that supported (and very much openly so) the Serbs during the Balkan wars. The author, reknowned Greek journalist Takis Michas, claims that this alliance was due in part to religion and a shared sense of history. Both Serbs and Greeks are Orthodox, and viewed the wars as an attack by the Muslim Crescent (with Greek's arch-rival, Turkey, somewhere in the background pulling the strings) and the Catholics (the Croats, Vatican, etc.). Serb chetniks helped defend against Nazi occupation during WWII. And something about ancient kingdoms allying at the border of the Ottoman and Hapsburg empires. Greek Orthodox priests visited and prayed with Greek paramilitary units working alongside Serb Chetnik forces, the same forces who committed some 90% of human rights violations during the war. In short, Greece likes Serbia.

In setting up an understanding of this alliance, Michas describes early in his book three facets of Greek ethnic nationalism (which he opposes to civic nationalism, or being Greek based on universal citizenship rights). Religion (Greeks hold on to the uniqueness of their Greek Orthodoxy), shared geneology (the Hellenic culture) and language (Greek).

I mentioned to my friend that this type of nationalism, in my opinion, was similar to that experienced in Israel, where language, shared geneology and religion plays a big factor in "Israeli" collective identity. If you are not able to fully enjoy these three qualities, you are not really Israeli. Just ask any Arab citizen of Israel. Al-Jazeera reported recently on Israel's immigrants, many of them children born and bred in Israel, who may be deported at the end of the summer back to their countries of origin.

My friend didn't much like the comparison, but questioned how someone who wasn't "really Greek" could become a citizen; with so few Greeks (11 million), allowing so many immigrants in would make Greece "less Greek". Apparently, she is on the conservative side of the debate that is raging over the PASOK (socialist) government's proposal to grant citizenship to all their immigrants. A good article by Douglas Muir points out that even the current Archbishop of Athens (the head of the Greek Orthodox Church), is actually an "Arvanite", ethnic Albanians incorporated into the Greek state at the time of independence. No one even realizes this, and he points it out to show that Greek culture is not static and is capable of admitting many cultures and still retaining its identity.

To be fair, proportionately, in seems as though Greece is taking in the lion's share of undocumented workers. For a cash-strapped country, that can cause a heavy burden. (UPDATE: Thanks to Carmen for pointing out the idiocy of this previous statement.In her words, "anti immigrant movements are racist and always have been." I agree and pardon the previous statement). I remember as I crossed the Turkey-Greece border, there was one black youth on our bus. As soon as we entered Greece, I knew there would be problems when the border police started looking at him sternly. He was taken off the bus and detained, on the suspicion that his passport was fake.

Of course, not everyone shares my friend's point of view. Last year, after a Pakistani youth died in police custody, people took to the streets and battled the police. At least among the anarchists, it was seen as another example of the police brutality that caused massive rioting in December 2008. On March 20th, there will be demonstrations held for allowing immigrants - children especially - to become citizens.

Greek society seems to be super dynamic, and changing everyday. The strikes called against the EU and the privatization schemes as a response to the debt are constants. There was an uproar over a recent suggestion by German MPs that Greece should sell some of their islands, an overtly imperialist and patronizing statement that sent Greeks running around rumoring a second German occupation of the nation. This Thursday is another strike here in Thessaloniki and I'll be sure to be there.

Meanwhile, popular 'expropriations' of food are still being carried out against large supermarket chains, and in Robin Hood style, the goods are being distributed in needy communities. Enjoy the video!

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

"A Letter Home", from Palestine

A friend from the International Solidarity Movement, the group I was involved with in Palestine, wrote a beautiful letter about the recent events in Palestine. It makes me cry, and I would like to share it with all of you.

___________

Hi All,

I hope this letter finds you well.

A brief note: It has been brought to my attention that people were reluctant to forward or respond after news of the raids in February. Anything I send out is intended for as massive an audience as possible, and it’s really critical that people continue to do the great job that they have done of forwarding on. Similarly, I really appreciate hearing from people and your emails in no way endanger either of us.

I’m sorry it’s taken me so long to write a new update. To be entirely honest, things have been increasingly difficult and the thought of writing home has been too intimidating to even consider.

This morning as I watched the sun rise over Sheikh Jarrah, I finally found a way of verbalizing what it is that’s been going on.

Events I reference: Bulldozer destruction near Bethlehem to build the apartheid wall: http://palsolidarity.org/2010/03/11629

The shooting of Ehab Bargouthi, age 14: http://palsolidarity.org/2010/03/11666

The destruction of Bidya’s natural spring: http://palsolidarity.org/2010/03/11679

The beating by riot police of five ISM activists (myself included) on Saturday night following a Sheikh Jarrah solidarity demonstration. We were standing on a sidewalk. This story hasn’t been published yet due to legal considerations; check the website in the next few days.

A Letter Home

There are moments where I just can’t take it in. Palestine—something tangible that you could hold in your hand—or more precisely, something slipping between your fingers before you can really know what it is you’re losing. Something beautiful. We are witnesses to more destruction than we will ever comprehend.

I watch the girls walking to school in their navy uniforms and I wonder how they fit into Israel’s 100 year plan.

I sit in the fig tree in Sheikh Jarrah and wonder if Saleh will be able to collect the fruit that ripens this autumn.

The al-Kurd house is in court tomorrow. When the petals fall from the roses blooming in the walkway, who will sweep them up?

Ehab’s chest rises and falls with the steady force of the ICU respirator. His olivey feet, scrubbed impossibly clean, reach beyond the wadded up sheets. Somehow they are perfect and human. A reminder of the entire person hidden behind the head swaddled in a manner reminiscent of playing “mummies” with rolls of toilet paper. Whether he will live or die is anyone’s guess. And I am told to approach his anguished mother with “Alhemdullileh, Allah salamtu”. Praise God. Thanks God everything is always ok.

On a live Rachel Corrie special for Tulkarem TV, I take a deep breath and promise the cameras that the American people are good. That we don’t know what we are doing and if we did, we would stop. In that moment and in every breath before and since, I am begging and pleading the gods I don’t believe in—please, somehow, could this be true. Would we stop? Can my home place, with its glacier-capped peaks and loamy farmland, ever understand the horror of bulldozers the size of two-car garages gently scooping ancient olive trees out of the pungent earth? Can my people ever see that they give $20 to Oxfam to rebuild the school their year-end taxes destroyed? No stack of Benjamins can reconstruct the children plucked from this god-forsaken holy land, each as fragile and loved as Ehab.

As the settler father leaves the house this morning, he carefully pushes his daughter’s stroller with one hand; closes the gate and then tugs his shirt over the pistol at his waist with the other. Who are those bullets for? The mother of five who sits in a plastic lawn chair across the street from her home? Her son, 20, who watches his father routinely arrested for refusing to allow his dignity to be swept away with last night’s bonfire ashes?

We can stand in the secluded basin, the sun beating down on the olive trees, but it’s too late to stop the five pale-legged Israelis dumping bag after bag of concrete into the village spring. The soldiers protecting the sun-hatted settlers make us close our cameras—it’s a Closed Military Zone. They stare, arms crossed, as I search their faces for an answer. Does any one of them truly believe that “security” justifies gratuitous vandalism? One dark-eyed boy is surely no older than I. If only he could know the hospitality which advises me, “You are welcome in your home”. If only he could hold sleeping five-year-old Samaa, her dark hair fanned out across the blankets, and wonder if she will live to see al-Aqsa. If only he could know that after the riot cops beat us Saturday night, someone produced a giant box of sandwiches. Would he ever again protect the destruction of something so simple and pure as a natural spring?

Palestine is slipping through our fingers. Every one of my International friends (family?) has dissolved in tears this week. Most of our friends in Sheikh Jarrah have been, or live in fear of, arrest for resisting the confiscation of their family homes. Four have been arrested in the past 36 hours.

I will never forget the feeling of being violently ripped from my friends, both Palestinian and International, as we were beaten to the ground that night. In a tangle of arms reaching for each other, being dragged by the hair as others’ heads were kicked like soccer balls, I realized I felt no concern for my own safety. The safety of the people I love; the communities we belong to; are frighteningly threatened. If there should be anything for little Samaa to grow up to; any figs for Saleh to collect this fall; any reason for Ehab to awaken from his coma; we must act in ways stronger than a few dollars carelessly tossed at erasing Israel’s destruction.

We must end systems that use bulldozers to smash swingsets in order to build walls of 25-foot-high concrete slabs. We must act to redirect your income from planting a bullet in Ehab’s skull. We must act because Palestine is slipping away, and there is no way to describe the beauty of an olive grove or a spring or a teenage boy. These are things that America destroys without knowing.

Shukran, Thanks,

E.S.

ISM reports: palsolidarity.org

What can you do? bdsmovement.net

Film showings are always a great idea. Occupation 101 and Peace, Propaganda and the Promised Land are available at freedocumentaries.org

Every U.S. man, woman, and child, gives roughly $8/year for Israeli defense spending.

Every U.S. taxpayer gives roughly $18/year for Israeli defense spending.

Monday, March 1, 2010

A Glimpse into the Netherworld of Jordanian Industrial Zones

I remember once when I was in Beirut's Hamra district, waiting for a take-away order of corn and ketchup breakfast pizza (it's tastier than it sounds, trust me). This tiny woman in a short, pink dress was ordering bread from the owner, who was attempting to seduce her with big grins and flour on his face. She definitely was south-asian, and my curiosity got the better of me.

"Are you Sri Lankan?" She sheepishly smiled and said yes. We talked a little bit more about where exactly she was from, about my background, and I think I tried to throw in a little bit of Singhalese, in vain. Well, nothing happened; she got her bread, I got my strange pizza, and we went our separate ways. But I had heard so much about slave-labor conditions of Asian immigrants in the Middle East that this encounter left me wondering, I wonder what she goes through.

Yesterday I left Palestine, passing Jericho on the Rehavam Ze'evi highway and crossing the Jordan valley over the King Hussein Bridge. (Just a sidenote about that highway: Rehavam Ze'evi was the ultra-right wing Minister of Tourism who supported the idea of forced relocation of Palestinians. He was assasinated by a PFLP hit-squad in Jerusalem in 2001, in revenge for the assasination of PFLP leader, Abu Ali Mustapha. The PFLP - Palestinian Front for the Liberation of Palestine - is in theory a Marxist organization founded in the 60s to fight Zionism and is considered a terrorist organization by the US of A; the Abu Ali Mustapha Brigades is the military wing. The highway, ironically, is given Ze'evi's nickname, "Gandhi", not because he promoted non-violent resistance to occupation, but because as a bespectacled lad in the army, he was skinny and the nickname stuck.)

The rains were heavy as I got into Amman, but today they eased up. I have always thought Jordan to be boring, an Amman is just one big slab of concrete. People always tell me to go see Petra, and I'm sure it's beautiful, but that gets old after awhile. So I decided to take a peek at Jordan's free-trade zones. Of course, I haven't read enough or been here long enough to openly pass judgement, so I will do so silently. (Free-trade zones = slave labor? At least, that's the story, right?)

I had just visited the tomb of the historic PFLP founder, George Habash, located in a quiet Christian-only cemetery just east of the Sahab suburb of Amman. Sahab is a industrial zone area, a dirty, glum concrete jungle. The industrial park stretches for miles, with 18-wheelers constantly coming in and out of guarded compounds, headed for neighboring countries by land, or to further destinations, leaving their goods at Jordan's Red Sea port city of Aqaba.

My taxi driver was confused when I told him to drive into the Al-Tajamouat Industrial Zone. The security guards seem to be bored and just nodded at us. Al-Tajamouat got a lot of bad publicity after the US-based National Labor Committee ran a series of articles and publications about sub-human work conditions at the zone; you can read more here. The managing director was trained by USAID after Jordan and the US signed a Free Trade Agreement in 2000. I walked around. There were many closed restaurants, with signs written in Hindi and English, proclaiming that they served authentic Indian, Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan food. There are a few international call centers, offering calls to Sri Lanka for .02 dinars a minute (about 3 US cents). And of course, there is a Western Union, the scavenging vultures of the capitalist world.

I walk into a small store. Two middle-aged men, speaking Bengali, are buying some cardamom and some other spices. There are plenty of spicy red chilies for sale, and I see a bottle of woodapple jam, bottled by that ubiquitous Sri Lankan brand, MD. Then my eyes light up as I spot a package of Lemon Puffs. After so many years, that yellow package can still make my mouth water (screw you, Switzerland). I buy a pack.

The owner is a Bangladeshi, and we converse in broken Arabic and English. When I ask him about how conditions are here, his smile fades and he stops talking. Then he says "Ok, bye bye". I take that as an invitation to leave. Maybe I smelled bad. Or maybe he was worried that I was an informant.

I continue to walk around. Lots of buildings with small windows. At one building, hundreds of people are pouring out. They seem to be workers, all South-asian, mostly men, but with a few women as well. I walk in where the workers are leaving. At the end of the corridor, a security guard is locking the door as the last worker leaves. The worker spots me and directs me back out. "Problems for you", he says quickly in broken Arabic. "Are you Sri Lankan? Looking for work?"

Amusing that he thinks that this hippie-looking little pansy appears to need a job. No, I confess, but how is work here? "Not good," he mutters and quickly walks away. I overhear a group of women speaking Sinhalese, and I ask them where they are from. Colombo. They ask me what I am doing here. I tell them that I heard about this place and wanted to find out how life was here. They say "fine" and then "ok, bye bye."

I decide not to enter the buildings labeled "Dormitory K" and "Dormitory J". That seems too personal, too soon. I walk past another restaurant, where a group of men are standing around a delicious smelling pot of curry and dipping in and laughing. I wanted to eat, but felt that maybe I should let them relax and enjoy without having a nosy trouble-maker poking around with Lemon Puffs in his hand.

Well, I'll leave you all with a link to this video by the National Labor Committee, called "The Hidden Face of Globalization".

"Are you Sri Lankan?" She sheepishly smiled and said yes. We talked a little bit more about where exactly she was from, about my background, and I think I tried to throw in a little bit of Singhalese, in vain. Well, nothing happened; she got her bread, I got my strange pizza, and we went our separate ways. But I had heard so much about slave-labor conditions of Asian immigrants in the Middle East that this encounter left me wondering, I wonder what she goes through.

Yesterday I left Palestine, passing Jericho on the Rehavam Ze'evi highway and crossing the Jordan valley over the King Hussein Bridge. (Just a sidenote about that highway: Rehavam Ze'evi was the ultra-right wing Minister of Tourism who supported the idea of forced relocation of Palestinians. He was assasinated by a PFLP hit-squad in Jerusalem in 2001, in revenge for the assasination of PFLP leader, Abu Ali Mustapha. The PFLP - Palestinian Front for the Liberation of Palestine - is in theory a Marxist organization founded in the 60s to fight Zionism and is considered a terrorist organization by the US of A; the Abu Ali Mustapha Brigades is the military wing. The highway, ironically, is given Ze'evi's nickname, "Gandhi", not because he promoted non-violent resistance to occupation, but because as a bespectacled lad in the army, he was skinny and the nickname stuck.)

The rains were heavy as I got into Amman, but today they eased up. I have always thought Jordan to be boring, an Amman is just one big slab of concrete. People always tell me to go see Petra, and I'm sure it's beautiful, but that gets old after awhile. So I decided to take a peek at Jordan's free-trade zones. Of course, I haven't read enough or been here long enough to openly pass judgement, so I will do so silently. (Free-trade zones = slave labor? At least, that's the story, right?)

I had just visited the tomb of the historic PFLP founder, George Habash, located in a quiet Christian-only cemetery just east of the Sahab suburb of Amman. Sahab is a industrial zone area, a dirty, glum concrete jungle. The industrial park stretches for miles, with 18-wheelers constantly coming in and out of guarded compounds, headed for neighboring countries by land, or to further destinations, leaving their goods at Jordan's Red Sea port city of Aqaba.

My taxi driver was confused when I told him to drive into the Al-Tajamouat Industrial Zone. The security guards seem to be bored and just nodded at us. Al-Tajamouat got a lot of bad publicity after the US-based National Labor Committee ran a series of articles and publications about sub-human work conditions at the zone; you can read more here. The managing director was trained by USAID after Jordan and the US signed a Free Trade Agreement in 2000. I walked around. There were many closed restaurants, with signs written in Hindi and English, proclaiming that they served authentic Indian, Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan food. There are a few international call centers, offering calls to Sri Lanka for .02 dinars a minute (about 3 US cents). And of course, there is a Western Union, the scavenging vultures of the capitalist world.

I walk into a small store. Two middle-aged men, speaking Bengali, are buying some cardamom and some other spices. There are plenty of spicy red chilies for sale, and I see a bottle of woodapple jam, bottled by that ubiquitous Sri Lankan brand, MD. Then my eyes light up as I spot a package of Lemon Puffs. After so many years, that yellow package can still make my mouth water (screw you, Switzerland). I buy a pack.

The owner is a Bangladeshi, and we converse in broken Arabic and English. When I ask him about how conditions are here, his smile fades and he stops talking. Then he says "Ok, bye bye". I take that as an invitation to leave. Maybe I smelled bad. Or maybe he was worried that I was an informant.

I continue to walk around. Lots of buildings with small windows. At one building, hundreds of people are pouring out. They seem to be workers, all South-asian, mostly men, but with a few women as well. I walk in where the workers are leaving. At the end of the corridor, a security guard is locking the door as the last worker leaves. The worker spots me and directs me back out. "Problems for you", he says quickly in broken Arabic. "Are you Sri Lankan? Looking for work?"

Amusing that he thinks that this hippie-looking little pansy appears to need a job. No, I confess, but how is work here? "Not good," he mutters and quickly walks away. I overhear a group of women speaking Sinhalese, and I ask them where they are from. Colombo. They ask me what I am doing here. I tell them that I heard about this place and wanted to find out how life was here. They say "fine" and then "ok, bye bye."

I decide not to enter the buildings labeled "Dormitory K" and "Dormitory J". That seems too personal, too soon. I walk past another restaurant, where a group of men are standing around a delicious smelling pot of curry and dipping in and laughing. I wanted to eat, but felt that maybe I should let them relax and enjoy without having a nosy trouble-maker poking around with Lemon Puffs in his hand.

Well, I'll leave you all with a link to this video by the National Labor Committee, called "The Hidden Face of Globalization".

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)